what is a waterfall?

This month, we build on our “explain the change” challenge, as we bring you another article from our back-to-basics series called what is…?, where we break down some common topics and questions posed to us. We’ve covered much of the content in previous posts, so this series allows us to bring together many disparate resources, creating a single source for your learning. We believe it’s important to take an occasional pulse on foundational knowledge, regardless of where you are in your learning journey. The success of many visualizations is dependent on a solid understanding of basic concepts. So whether you’re learning this for the first time, reading to reinforce core principles, or looking for resources to share with others—like our comprehensive chart guide—please join us as we revisit and embrace the basics.

In our workshops, we often put a grid of a dozen charts up on the screen, and say to the participants, “Most of the charts you’ll need to communicate effectively in business are right here on the screen. 99% of the time, one of the visuals you see here will get your message across effectively. And as you can see there aren’t any really unusual charts here. You’ve probably seen all of these before.”

If, at this point, somebody in the room says, “Actually, I’ve never heard of a ______ chart before,” you can almost always fill in the blank with the word “waterfall.”

One reason this happens is because waterfall charts are very effective in specific use cases—typically, showing the positive and negative components of change—and are frequently relied upon in particular industries. So, if we happen to have a workshop where the attendees are from the financial services or insurance sectors, or work in human resources, then attendees are likely familiar with the waterfall chart. Outside of those use cases and/or those industries, however, they’re seen infrequently, if ever.

In this article, we are going to demystify the waterfall chart: explain what it is, when we should use it, how to read one, and ways to avoid common pitfalls when creating our own.

What is a waterfall chart?

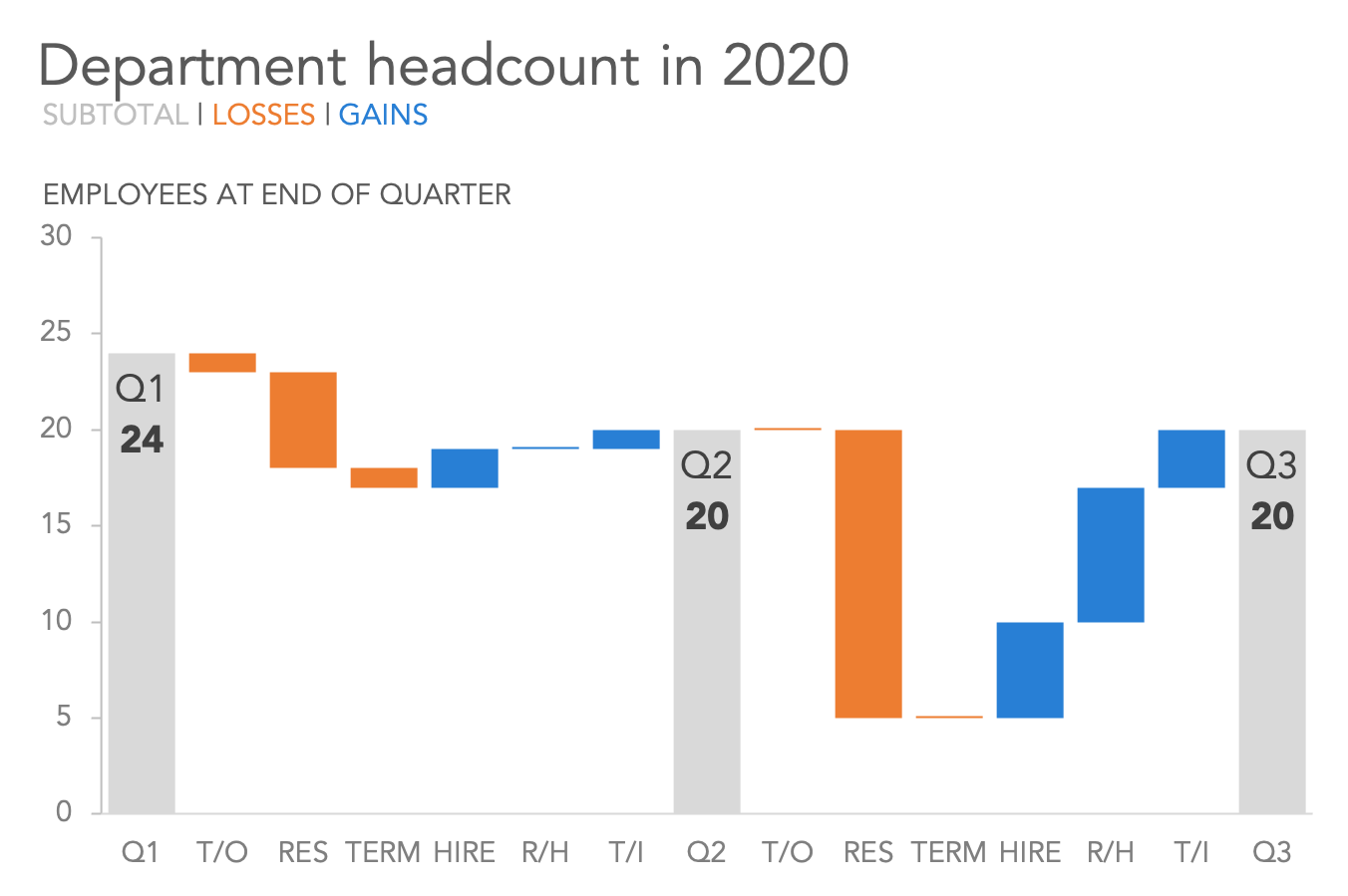

A waterfall chart is a specific type of bar chart that reveals the story behind the net change in something’s value between two points. Instead of just showing a beginning value in one bar and an ending value in a second bar, a waterfall chart dis-aggregates all of the unique components that contributed to that net change, and visualizes them individually. The following example is from storytelling with data.

The waterfall chart gets its name from its shape. Usually, the first bar in a waterfall chart starts from a baseline of zero, and represents the initial quantity of the measure in question. Then, there are a series of smaller bars, seemingly floating in space (often rising to a peak, and then falling down towards the baseline), leading up to one final bar, which represents the ending quantity of our chosen measure, and (like the first bar) starts from the zero baseline of our x-axis.

The waterfall chart is a good way to show the complexity that can sometimes be hidden in our cumulative numbers. If I am in human resources, and I see that last year in January your department had 20 people in it, and this year in January your department still has 20 people in it, it doesn’t necessarily look like anything interesting has happened.

But if I can visually represent every component of the change in staffing levels over the course of that year, then I can show you that in fact, 15 people quit during the year, and to balance that out we had to hire 10 new people and transfer in five from another department. Compared to a bar or a line chart, the waterfall chart tells me a more complete (and possibly alarming) story.

How does a waterfall chart work?

One of the very few golden rules of data visualization is that your bar charts all have to have a common baseline of zero. This is still the case in a waterfall chart, but it only applies to the first bar that shows the initial value, and the last bar that shows the final value. (Or, if you prefer: the “before” and “after” values.) The baselines of the component bars between these totals are all different, and are dependent on whatever the running total is. Put another way: for the pieces in the middle of a waterfall chart, the end of the previous bar is the baseline of the next one. The appearance, then, is of a staircase moving up and down, connecting two (or more) pillars.

The concept is simple, but because we’re not used to seeing bars floating in space, audiences can sometimes find it challenging to interpret the waterfall at a glance. One complicating factor is that sometimes the “baseline” of these component bars is at the top of the bar (if that component is showing a negative value), when other times it is at the bottom of the bar (for positive values).

To further complicate things, waterfall charts can include multiple periods of time. A waterfall that shows changes across multiple quarters of the year could have more than two “pillars:” one showing the initial quarter’s total, and then one more pillar for each of the subsequent quarters. Between these pillars, we have several distinct regions of component bars showing the gains and losses from those periods. Rather than a waterfall, we’ve now created a series of arches (if you order first by gains, and then by losses) powerlines (if losses are shown before gains), or zig-zags (if we didn’t order our components at all).

There are a couple of ways to make waterfalls clearer. Some people prefer to make bars showing increases a different color from bars showing decreases; some people prefer to draw horizontal lines connecting the edges of bars to give your eye a line to follow as you move from left to right through the chart, making the stair-step pattern easier to trace across components.

Where do we see waterfall charts used?

The waterfall chart is often seen in human resources, to show attrition and growth in hiring (see an example here.) It is also commonly used in the financial industry, to show credits and debits, gains and losses, over the course of a single period of time; and in industries where keeping a running tally of active accounts or subscriptions—or revenue from these—are core to the business.

Are there any unusual variants on the waterfall chart?

The main variant is the waterfall chart with multiple totals in it, as referenced above. It changes the visual effect from a single cascade into multiple arcs; technically still a waterfall chart, but no longer fully reminiscent of the name.

There are charts that use a similar visual effect, where each subsequent mark on the x-axis of a bar chart shows a net change, rather than a cumulative total. Sometimes this is used in a modified Pareto chart, an example of which is shown here.

The more common Pareto chart is a combination chart, where a bar chart shows the absolute quantity of each category, sorted in descending order, while a line chart shows the cumulative percentage of the overall total covered by the current and all preceding categories.

Pareto charts only include positive values, depict categories that add up to 100% of a total, and sort these categories along the x-axis in descending order of value. The intent is to show how few categories are necessary, when sorted in this manner, to reach 80% of the total value. (The “Pareto principle,” otherwise known as the 80/20 rule, posits that 80% of the total consequences in a system are attributable to just 20% of the causes.)

Stock charts, which show daily open, high, low, and close values for a particular security, are somewhat related, but would not truly be considered waterfall charts; although they too often show component bars floating in space, they have more in common with box-and-whisker plots.

What are some drawbacks to the waterfall chart?

By its very nature, waterfall charts ask people to compare the lengths of objects that are floating in space. We are good at comparing the length of lines if those lines share a common baseline, but in a waterfall chart, very few of the bars do. Therefore, it’s hard to compare the specific sizes of growth or contraction between two subcategories. In cases where the specific values of component pieces are important to convey, directly labeling those pieces is advisable.

There’s also the aforementioned challenge that some bars are meant to be read bottom-up (the baseline is at the bottom) and some top-down, depending on whether they are showing gains or losses, respectively. This is easier to mitigate if we group all of our gains and all of our losses together (ensuring that the chart maintains a regular arched or bowed shape); however, if we have subcategories sorted such that gains and losses are interspersed, the insights we might take away are harder to parse out.

One last challenge of the waterfall chart is a challenge for its designer, and it’s one that is true whenever we need to show large and small values together: the temptation to truncate your Y axis. It’s not uncommon for the “pillars” of waterfall charts to represent HUGE numbers (current valuation of our multinational conglomerate, for instance), while the component pieces representing a weekly or monthly change are comparatively tiny….maybe 1% or less of the total values.

The human resources example I gave you earlier started with only 20 people in the department. What if I started instead with 2000 people, but we were still only gaining or losing 10 or 15 people in any given category? It would be difficult to perceive those changes in a waterfall chart.

You might think that it would be fine to “zoom in” on the interesting part of the waterfall chart: the components of change. We can’t do that, though, because this totally negates the value of using a bar chart in the first place. Bar charts encode quantitative value in the length of the bar. That is why it must start at zero.

In cases like this, it can be better off if you use a bar of zero length as your starting point, and just show the changes over time and then a final bar that shows the net change from the prior. You can then use text to write the actual number of the value of the starting amount.

If I’ve never seen this kind of chart before, do I really have to learn about it? Doesn’t that mean that my industry probably doesn’t use it?

While somewhat uncommon, a waterfall isn’t so esoteric that it should be ignored. At its core, it’s a specific variation of a bar chart, which is one of the most common data visualization types out there. Moreover, a waterfall chart is very good at performing its specific task: showing the component pieces of an overall change. When the summary statistics aren’t doing a great job of telling the true story, it can be very helpful to have a defined way to show the composition of change between two points (which we might otherwise turn to line graph to show, while still maintaining a sense of quantity that a bar chart does a much better job of providing).

If you have yet to be asked to create or read a waterfall chart in your current role, it’s unlikely that one will suddenly become part of your everyday responsibility. But in this particular use case, when you want to explain the change between a starting value and an ending value in more detail, a waterfall chart can be extremely useful.

How do I make a waterfall chart?

Now that we’ve explored the waterfall chart and looked at potential use cases, you may be wondering, “How do I actually make one of these graphs?” Tableau users will notice that waterfalls don’t come “out of the box,” so you will need to be a little creative to achieve this look, leveraging the Gantt mark type. In earlier versions of Excel, invisible stacked bars, propping up the components of change, were often used to complete the waterfall look. Nowadays, waterfalls are part of the standard package of charts within Excel.

And while it’s an easier task to create your waterfall, there are several steps we’d recommend taking to transform them from the default output to something more aesthetically pleasing. To explore this transition in more detail, check out the video below.

You can continue your journey through our full what is…? chart series by browsing other common visuals like lines and pies, or explore our comprehensive chart guide page for additional chart types.