use cases for stacked bars

I recently penned a post asking the question, "Is there really a good use case for the stacked bar?" I highlighted a couple of examples where I've used them, but also the realization that I was remaking most stacked bars encountered in workshop settings into something else. I invited reader opinions and examples of where you have seen or are using (non-100%) stacked bars. In this post, I'll recap what you shared with me.

There were definitely some similarities and recurring themes in the comments I received. A number of people mentioned limiting the number of categories in the stack and highlighted the importance of putting the piece of most interest at the baseline so it can be easily compared across categories. It was noted that stacked bars may work better in an interactive environment, where you can more easily focus on one piece in the stack at a time (and restack as needed). There were also a couple of constraints mentioned that might warrant the need for a stacked bar: where the audience is adamant they want all the data, or when you have limited space and so need a multipurpose visual that can show multiple takeaways. There were also a couple examples of stacked bars gone wrong, or what not to do. Interestingly, even while making the case for stacked bars, some people turned them into something else (for example, unstacking the bar so each category has its own baseline, into a series of simple bar graphs), or used a 100% version to make their point.

There were also a few articles shared for those reading who are interested in more (the titles alone illustrate some varying views on this topic!):

Alberto Cairo "stacked bars and small multiples"

Andy Cogreave "vizzing the UK Election: rethinking stacked bars with ghost marks"

Robert Kosara "stacked bars are the worst"

Steve Wexler "how to take the screaming cats out of stacked bars and area graphs"

When I reflect on my experience with stacked bars and weigh the comments and examples received, I can sum it up to say there are indeed good use cases for stacked bars. Be careful, however, because they are often misused. One risk, as I mentioned in my original post, is that if there's something interesting happening further up the stack, it can be difficult or impossible to see since it's stacked on top of other things that are also changing. As always, consider what you want to enable your audience to do with the data and step back and think about whether the visual you've created allows for this with ease.

Following you'll find the specific examples and comments received (in reverse alphabetical order by first name, just for kicks; I received input through a number of channels, so if I missed yours, I apologize for the oversight!). Big thanks to everyone who shared thoughts and examples!

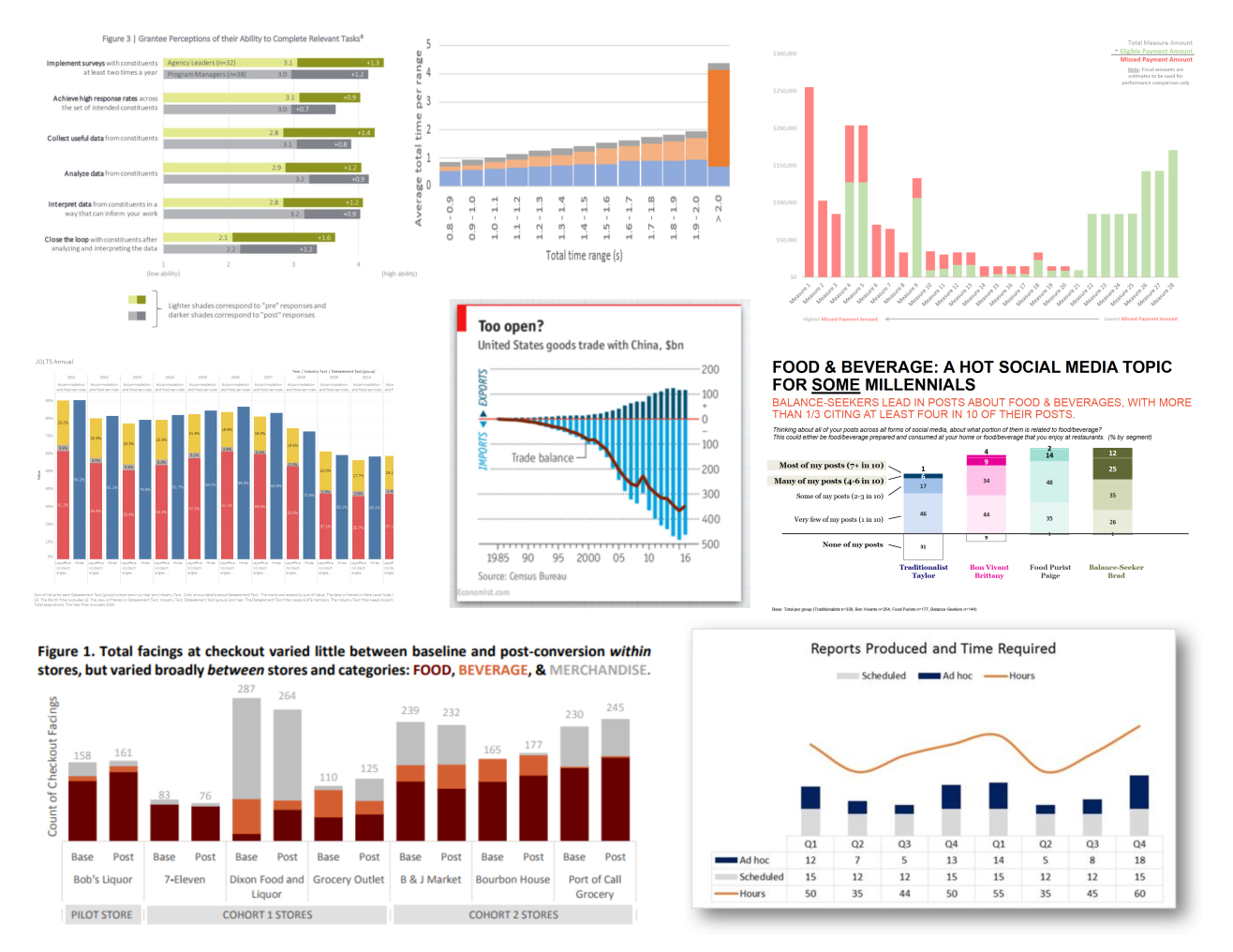

Ziwei says: It happens that I use stacked bars frequently in my daily work (I created some toy data and uploaded the Python scripts here) Here is an example:

Steve (who also recently blogged on the topic of stacked bars) writes: With a plain stacked you can also compare overall as well as within that one segment that is along the baseline. With a 100% stacked bar chart there is no overall comparison, but you can compare the outer element as there are now two common baselines.

So, what’s not to love about stacked bar charts?

Of course you know the answer as you can only compare one segment with a regular stacked bar chart and two with a 100% stacked bar chart. Sadly, we see those horrible marketing pieces that have lots of multi-colored segments. For me, the real value is when you highlight the selected region only, along with the ability to sort overall or sort by the selected region. I guess the key thing here is being able to move the region of interest to the baseline.

Steve shares the following example (by Matt Chambers, here is Tableau Public version, see the stacked bar in the middle of the dashboard), commenting, "This just nails it for me – I can easily compare overall punches as well as the punches that landed. No wonder McGregor lost – he exhausted himself throwing many more punches but landing far fewer."

Russell tweets: I find they work well for "total T is driven by change in A, B" narratives where most categories are (reasonably) constant (and displayed at the bottom).

Robert F. says: I have to stare and stare and reference and stare and stop and think and stare WAY too much with stacked bar charts. Too complex for a visual snapshot in my view. My thinking is I should, at a glance, get a decent idea of the idea you're conveying without having to look too intently.

Robert C. tweets: The more I think about the more it bothers me, but could you see utility in stacks displaying average monthly spend by company, dept., team... etc? I still wouldn’t stack those though. What about the scenarios where you want to see individual contributions, but what really matter is hitting the goal? Example: fundraising. Showing the individual contributions matters, but so does the goal.

Pete shares: I'm pleased to attach the example of a stacked bar chart I used in a research presentation done for a client last year. You'll immediately see that I applied or adapted a number of your SWD principles to the design of the chart (or at least tried to!), because those principles have always made strong intuitive sense to me. A few notes to that point and to other aspects:

The aim of the slide was to draw audience attention to the strong use of social media by "Balance-Seeker Brad" relative to usage by the three other Millennial segments surveyed in this research. I used a monochromatic scale for each of the four segments, with dark shading, along with bolder and larger numbers, to draw audience eyes accordingly.

Placing the most frequent usage of social media at the top of the stacks seemed unavoidable, since the answer scale ran from "None of my posts" (charted below the "zero" baseline) to "Most of my posts." However, this didn't seem to hinder the visual tracking we wanted.

The passage of time was not an factor in this chart, which simplified the task.

Mike D. tweets: Stack bars conflating 2 very different questions: how are we doing and what's the problem. Keep them separate!

Mike G. says: I find the stacked bar useful only when there are two groups in the stack. As you state, once there are more than two I can no longer compare the 2nd and 3rd groups. That was my first thought when I saw the development priorities example in your book. If I cared about the middle or last group, that did not help.

I understand that the 100% stacked gives me a second baseline, but I think that still takes some mental gymnastics to read the graph upside down to compare the top groups. That is probably easier on a horizontal rather than vertical.

So I use the 100% stacked bar only when I have two groups in the stack and I am showing a percentage of the whole. The two groups can be male/female or republican/democrat. Sometimes people want to see percentages as a part of the whole, rather than just a bar chart of percentage complete. In such cases, the complete would be one color and the second group of "not complete" as another color (light grey).

I find the non-100% stacked chart a little more useful because it allows me to see overall numbers via stack height and still get the % of the whole. In these cases, I still only use two groups.

These personal guidelines drive my decisions on pies as well. The stacked bars are much better for comparisons, but I still will only use two groups in a pie (3 tops).

MF tweets: How about A stacked bar showing total sales by channel, and there are inly two channels or three the most. And the key concerns is the total sales, while the secondary information is contribution by channel. To supplement that we put the % on the bars as data label.

Melissa says: I’ve include a screenshot below (from pg. 13 of this report) of a time when I think my use of stacked bars worked well. From my perspective, the horizontal bars show change over time (pre vs post), but also allow you to compare between the two groups (agency leaders vs program managers). I am not sure I would use a similar format with more than two categories (in this case, pre vs post).

Matthew shares: My advice to clients and the team internally is very similar to yours. Non 100% stack bars are not the most effective representations. Similar to what you mentioned, I prepare to break it up into 2.

We have also evaluated when would a non 100% stack bar work. More recently Microsoft Power BI introduced something they called a Ribbon Chart. It is basically a non 100% stack bar that looks at volume changes across time to determine which is a larger number. I think it is good to see if what are the biggest issue that might arise across time (might be better than a 100% stack bar because the ability to have the largest number appear on top).

Leonard writes: One place where I can see stacked charts having value is if you want to look at the total, and highlight the contribution of just one key component to the total. E.g. if your story is "Revenue is rising rapidly thanks to a dramatic increase in sales in China." You wouldn't even break out the other categories on the chart: just have China in blue and the rest of the bar coloured grey.

Kari shares: Although similar to your example….this is one I have learned how to make better from you. I have a client who is only concerned on whether or not their product can make a claim; however, they still want to see all other measures (or her team does). This is how I have highlighted the better and least well performing claims, but also providing the other info the rest of her team wants. (Product/attributes have been blinded.)

Note the colors I am now using. I will say my co-worker is not a fan of deleting the data labels that are not the story (I at least leave them in for checking purposes, and then delete them) – my client has yet to complain though!!

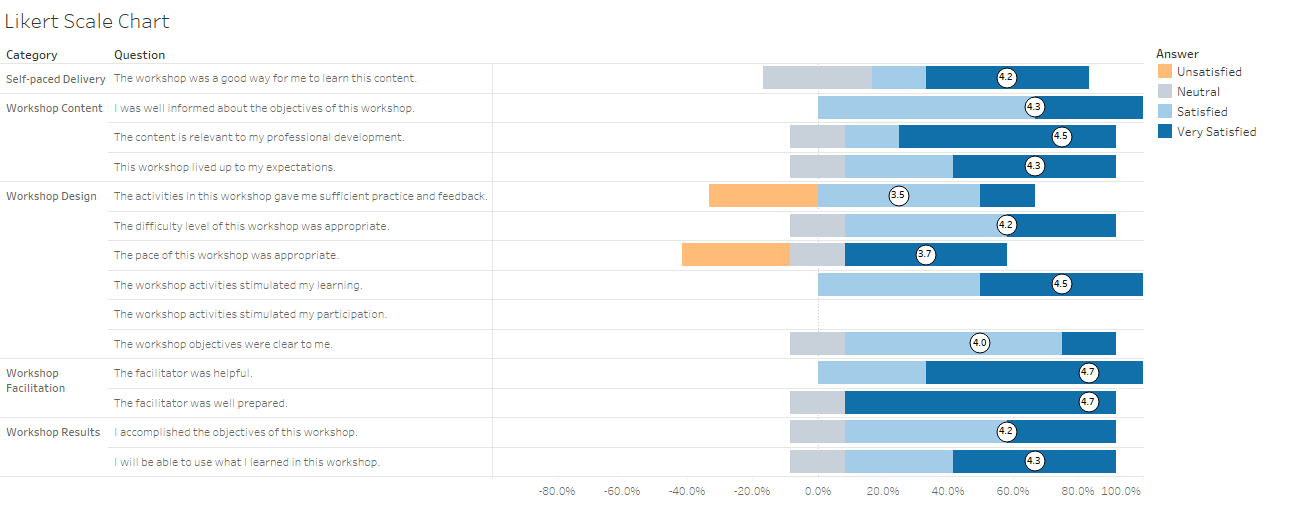

Jamie writes: I don’t have examples to share, but I do have an opinion on when stacked bars work well (including 100% versions), and that is when the categories are a scale with a logical order and a relationship between neighboring categories. Both your Chapter 6 “Top 15 development priorities” and your previous blog “Patients with Aglebazoba” examples fit this criteria. Other classic examples are survey questions of strongly agree to strongly disagree or very satisfied to very dissatisfied (although those tend to be 100%).

In these scenarios we are less interested in the individual categories than in the cumulative data, which is easy to see in a stacked bar. In your Chapter 6 example, the 10% who rate Poverty reduction 2nd most important is not useful data except in the context of the 15% who rate it most important. What we ask when we see data like this is “How many rated this most important?”; “How many rated this in the top 2?” and “How many rated this in the top 3?”. These questions are easy to answer with a stacked graph.

In your earlier revenue example, I assume the 5 revenue categories are discrete and so a viewer wants to see changes in a category unrelated to the others, which a stacked bar does not easily show.

The only time I think discrete categories work well for a non-100% stacked bar is if there are only 2 categories (or possibly 3 if the middle one is a neutral value such as “unknown”). For example, you might graph new hires by month, with a stacked bar showing male or female. As long as the data doesn’t fluctuate too much you could easily see the overall trend in hires, as well as any change in the gender balance.

Haim shares the following thought and example: When faced with using a stacked bar chart, I usually convert to a 100% chart instead; but it really depends on each specific case.

Gordon shares some examples of what not to do, writing: These examples will certainly be on your *DON’T* list of stacked bar charts. These are from 20 years ago with Excel 97 before I knew any better. I’ve attached the spreadsheet with the data. Long before Power Pivot we pulled data from our mainframes via JCL and had macros to create every tab. It took about 12 hours to run on those old Pentium machines.

This was an import-export data for everything entering and leaving the U.S. via Atlantic ports. The data came from PIERS (Port Import Export Reporting System). These samples are from the Germany Inbound tab. PIERS has an enormous amount of incredibly valuable data. Frankly it was very hard to put so many vital commercial data points into a format where a person can find what’s important to them without pivot tables or slicers. If you’re the Germany country manager how could we tell you your: competitors, customers, equipment, ports, commodities—in a way so you can quickly zero in on what’s important? So we basically took the kitchen sink approach.

Maybe this will serve as a reminder of how far we’ve come—or haven’t—with our data tools. Even with pivot tables and slicers it’s hard to get people actually click on something to filter what they need—so many want the data somehow served with just the information they need. Even today with PowerBI the data would still be like drinking from a firehose and yet so many ways to slice the data reveal incredible insights.

Glynn shares the following example and explanation (attributing the idea and instructions to Jon Peltier’s site).

1. The total monthly value is shown as the black bar. This can be compared against every other month by running down the black column (my real version has 30 months showing). I show the values on each bar as axes are not possible.

2. Each monthly value is split into various components (30 days, 60days, 90 days etc), again with the values shown.

3. Given that each component value starts at a common base line, comparisons can be made down each column. The baseline is created by dummy series with no fill and no borders.

4. The orange box (rolling 12 month average) is an additional set of data I have added and is sitting on the secondary axis.

5. One of the main issues with this type of graph is negative values. Note the -45k in the February 2017 90-119 days. Any value less than zero can only be shown as a zero otherwise it tries to print it to the left of the entire graph. I am picking up the data labels from formulae in additional cells, not the actual data cells.

Glenn shares: I don't have an example but stacked bars are fine with interactive software because you can usually select one of the dimension values if you want to see the trend of only that dimension.

Frank tweets: I think so. I wrote a blog about it. Stacking the bars in your favour!

FootyNumb3rs tweets, sharing the following example: I used stacked bars to breakdown soccer shots by outcome. Stacked bars are good for stats in which both the proportions and absolute value are of interest.

EvaluATE tweets: I like the staked bar if you use direct labeling. I agree that a separate legend makes it to difficult to read.

Eddie writes: Thanks for your sharing about stacked bars. In fact, it reminds me of my early article, which summarized several similar cases from The Economist. Especially, the stacked bars failed with negative contributions in Part 3. Note from Cole: see the "fail" graph Eddie refers to below; I've also included another he shows in the article linked above that I think does work reasonably well.

Debora shares: I use them when I need to show a varying total of various, fairly equivalent, groups over an extended period of time. The intent is to show the individual contributions to the total over the time period, providing one level drill down. IMO, they have rules to be optimal:

- groups of 5 or less.

- data points per group = 3x - 8x the number of groups.

- no group data average is less than 15% of the others.

- no large data fluctuations : <50% from one data point to the next.

- no ‘missing data’ holes in the middle of a group. The obvious exception is a group ‘appearing’ or ‘disappearing’ mid timeline.

- no data labels except maybe a TOTAL of all groups. (Requires a hidden second axis of exact frame overlying the primary axis graph.)

- color is a huge factor: it must support the story.

Daniel writes: Stacked bars are useful when "stacking/dividing" variable has an intrinsic order and all cumulative values from baseline make sense for that particular order. For instance, revenue across several products, divided by margin intervals (0-5%, 5-10%, 10-15%, …). The baseline bar (first stacked value) would be interpreted as Revenue for Margin between 0 and 5%, first two added bars would be interpreted as Revenue for Margin between 0 and 10%, and so on.

A similar graph using Revenue divided by Sales Representative can still make sense if Sales Representatives are ordered by rank (general sales volume for instance) and decoded cumulative values are the main subject of the story (for instance, “Top 3 Sales Representatives covered more than 80% sales of our top product, yet they covered less then 50% for next product…”).

Comparison between bars not sharing the same baseline is difficult. Robert Kosara wrote a post a year ago about it, mentioning Cleveland and McGill paper about graphical perception. While I believe that due intensive use of graphical devices, graphical perception has changed since 1984, I agree with the author that stacked bars are problematic because they mimic accuracy.

When stacked bars are used to encode individual values as part of a group, they will fail. When stacked bars are primarily used to encode cumulative values across a third variable with a intrinsic order, they will succeed even if the individual values comparison is difficult.

Dalton tweets, with the following example: As long as the visualization allows user to toggle to multiples I'm good with the story of the big picture.

Crystal shares: I wanted to send over an example of a stacked bar chart that we provide to our hospitals to assist in prioritization of quality measures. We needed a way to “normalize” measure data for quality measures in multiple programs to provide a single view of performance. We sorted on the missed payment amount in order to create a left-to-right/high-to-low priority listing—in this example the scale is important but not necessarily the exact amounts. I think if we weren’t able to apply our sorting criteria (i.e., if our x-axis represented time or something else we couldn’t rearrange) it wouldn’t work at all.

Charles comments: There are often other alternatives, but when you have few categories and do not need to focus on specific values, they might do the job. Mainly a plan B or C in my opinion.

Bryan says: I was experimenting with a stacked bar chart in Tableau, where I’m comparing different types of quits, layoffs, and other turnover data from the government, to the hiring rates for that year. Each set of columns for the year is the aggregation of the monthly percent of the work force that was either leaving or joining. So by comparing the stacked bar of voluntary and involuntary turnover to the single bar of new hires, I can see quickly if the industry was expanding or contracting, as well as the relative amount of voluntary turnover (in red) that may have been a factor in turnover overall. I think that might be an actual purpose for the stacked bar, even if it takes the creation of two different bars to compare to each other.

Brian writes: I’ve used something similar to demonstrate reports I must produce vs. ad hoc requests and the time commitment involved. Bottom-line is there was seasonality to when the unexpected came in and when times would be lighter (found out requestors took vacation right as schools broke for summer break). Data is purely fictional, but it conveys the general idea.

Bill tweets: When the total height of the bars is what REALLY matters & the legend is a secondary source of info (oh btw, most of the revenue came from Japan). Hard to leave as stand-alone without also enabling independent charts of the components... at least the one(s) that tell a story.

Ben's response to whether there's a good use case: Not if proper reasoning and decision making are required!

Berlinde says: I use only examples from my work to prove its effectiveness and thus hoping to spread the love for graphs…

We often need to represent the results of no less then 14 teams! Before, there was a lot of spaghetti, donuts and other colorful but often psychedelic visuals. I find myself reaching for bars quite often, even stacked ones.

The example I wanted to share, shows the results of queries closed in time (a KPI). The is no story or message included (yet), so the graph is still very much mere informative. The actual KPI bases itself on the total of queries of two types of tiers. I wanted to show the ratio between the two. I then got inspiration from the water graph from Bill Dean. To create a base for tier 2, I added a second axis. The second axis has the same range, so it is not discerned as an extra axis. I added the tier 1 on the second axis as a marker. It’s height is equal tot he difference between the total and the tier 2 bar. But as it starts from the same basepoint as those bars, there is a sense of comparison. The total bar and the tier 2 bar overlap.

There is still a lot of info on the graph, which might be too much. But this is also a desirability of my public. So this is me, searching for the middle ground.

Andy says: I defended the maligned stacked bar in the recent Data Debate with Andy Kirk. I've written about them before and how they support particular use cases. Check out the examples here looking at Tweets during the 2015 UK Election.

Andreea writes: Below are some samples of stacked bar charts from work. The first one is the result of a quick data analysis I did yesterday so see which of the software components is affecting the overall performance. The dark orange part is the result of the search. Both charts show the same data, but I think the stacked bar chart looks better.

The second sample is part of an automatic report. Here I cannot add a specific eye catcher because the data changes every week. The goal of these charts is for people to glance over them and quickly see if something went wrong. The software components (names and text removed) are color-coded. The table shows the exact numbers and the stacked bar charts show the overall performance, relative performance by component, relative performance by day and also a comparison with the last week (shades of gray).

Comments are very welcome. I'm a programmer and for me it was always natural to have tons of numbers and lines on a chart. That is until I stumbled upon your book and my view of charts changed forever. Many, many thanks.

Amelie tweets: IMO it is the pie chart of bars— works better when only 2 categories in the stack...

Alberto writes: Thanks for your posts and thought provoking subjects! Below is an example from a corner store healthy checkout conversion evaluation our team worked on. In this case we wanted to keep our final paper to 10 pages or fewer so we were limited in space. The stacked bar chart allowed us to convey several important messages in just one chart:

(1) That the total number of facings (items at checkout) did not vary much pre/post by store, but

(2) Varied quite a bit between stores.

(3) Since the total number of facings pre/post did not change much, it was easy to see that for some stores, the type of facings (food, beverage, and merchandize) did not change much from pre intervention to post intervention, while for others it did.

(4) It also allowed us to show that the predominant type of facing varied by stores.

Adolfo shares the following thought and visual: I think they work great on Likert Scale charts to show survey data because you can see to which end your respondents are leaning to. On other contexts I think they are useful if you keep your categories to just 2, maybe 3.

Big thanks again to everyone who shared their views and examples! If you have more to add to the stacked bar chart conversation, please do so by adding a comment below.