the structure(s) of story

The way I think and talk about story has evolved more over the years than any of the other core lessons that we teach at storytelling with data. Perhaps this is because there’s not a single way to characterize the complex nature of story. Rather, there are a number of manners in which this can be done, from simple to more sophisticated—with elements to be learned from each approach when it comes to how we can communicate effectively with data and in general.

I had to laugh to myself at the coincidence earlier this week—already having this topic in mind—when my son’s first grade teacher described story in her weekly video as being made up of beginning, middle, and end. This is exactly how I introduced story in my first book. It’s elementary, but a good place to start.

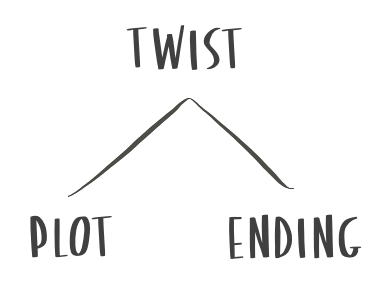

Aristotle is believed to have introduced this basic idea, proposing a three-act structure for plays. We can take our definition and accompanying depiction of story a step further, with the inclusion of tension. Tension lends shape: a rise and fall. So a modification on the linear beginning-middle-end construct that accounts more directly for tension could be a simple story mountain:

Where the plot is the context, what's happening when the story begins. This gets carried, onward and upward, to the twist. This is the main source of tension, something gone wrong that needs to be fixed. The ending solves that thing-gone-wrong and brings the story to its close, wrapping things up neatly. In our shorter workshops, we teach this simplified schema, due to ease of explanation and illustration in a time-constrained environment. You can practice diagraming a story along this and exploring parallels to business communications in our latest community exercise.

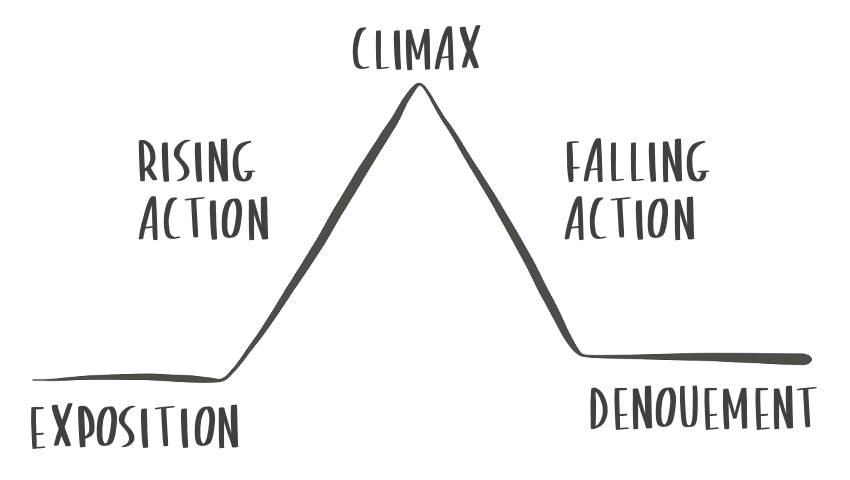

In my second book—and our longer workshops—story is explained via the more nuanced narrative arc:

Knaflic, Cole. Storytelling With Data: Let’s Practice! Wiley, © 2019.

Illustration by Catherine Madden.

Similar to story mountain, the first step in the narrative arc is the plot: where we are at the onset of the story. Tension is introduced through an inciting incident. This tension builds in the form of rising action, reaching its maximum at the climax, a significant turning point. Things relax over the falling action, a buffer that leads us to the resolution at the story’s end.

An older dramatic structure is likely the predecessor to this modern day narrative arc. German novelist and playwright, Gustav Freytag, expanded on Aristotle’s three acts, outlining a five-part model for successful storytelling in the 1800’s. Commonly known as Freytag’s Pyramid, it has similar components to the narrative arc, but is typically illustrated in a more angular form:

While the pyramid has basically the same pieces as the arc, different words are sometimes used to describe them. Exposition, to me, feels more thorough than plot (likely the result of the multi vs. monosyllable). I am partial to the French denouement (thought to be introduced post-Freytag), which suggests an unravelling of complexities (literally, “untying the knot”).

Whether arc or pyramid, these constructs are still each simplifications. They give you an idea of what's going on at a high level, however they don’t convey the full picture. In a good story, there isn't a single smooth ascent and descent—there are ups and downs throughout that move the story forward, carrying us, entertained, from plot to ending. While the twist or climax might reflect the primary conflict or maximum point of tension, there are typically numerous other issues introduced and resolved over the course of the broader narrative. It is precisely because of all of these ups and downs that the story holds our attention, keeps us guessing, and provides points of satisfaction along the way. The real story usually looks more like a jagged mountain:

It occurred to me recently, in the majority of our examples—in workshops, books, here on the blog—when we illustrate “story,” it’s often either the overarching story, the simplified view that follows the arc or pyramid, or it’s a single one of the jagged peaks from a broader narrative. Rarely, if ever, are we able to illustrate the full and complete story with all of the peaks.

This is the case for a couple of reasons.

First, there’s the time constraint. In a workshop or blog post or even in the books, we’re limited by how much time we have to set the context for an example and get into various nuances or storylines. Second, there’s the lack of context. We’re often visualizing data in areas outside of our immediate expertise and need to both make assumptions and generalize for communication to a broader audience. Third—and this is the most important and relevant to the conversation here—it’s rare that you actually need to tell the full story with every single peak.

Different audiences will care about different levels of detail. The exec might only want the high level arc or pyramid. The finance partner will be interested in a completely different set of peaks, combining into a widely varying storyline or narrative, than what you would use to communicate to the marketing lead. When we are the ones communicating, we generally need to have a good sense of all or most of the peaks, but then need to identify and weave together the specific combination that will work for our audience. It is exactly this idea that I explore further and illustrate via example—taking inspiration from one of my own favorite stories—in the recorded SWD community live event, “lessons from Oz: story in business.”

The next time you need to communicate in a data-driven way, consider the various structures of story put forth here. Determine which resonates with you or your situation and reflect on how you might use it effectively to communicate with your audience. Check out the diagram a story exercise in the community for some related practice.